This is not a sermon, just a fact: since I cut out alcohol 22 years ago, I’ve often awoken in the middle of the night with beautiful ideas, which is a golden gift for a writer, better than emeralds. Tuesday night, for example, I woke at 3 a.m., next to my sleeping wife, arose, dressed, slipped out of our hotel room in Minneapolis, and sat in the lobby with my laptop and started writing a book with a ten-word title about happiness. I’m a happy man, I am qualified. Last week I did two shows, just outside D.C. and in Vermont, two serious locations, and I made those people laugh so hard, they were glad they’d brought an extra pair of pants. I went to Minnesota hoping to solve a Medicare problem that I’d spent years on the phone about, listening to mind-numbing music on Hold, waiting to talk to a clueless functionary working from home, TV blaring in the background, dogs barking, and in Minnesota I went to an office, sat across the desk from a human being, the way we used to do, and he solved it in a matter of minutes. And he thanked me for my patience. Life is good.

I’ve been waiting a long time to become as old as I am and it was worth the wait. You couldn’t pay me enough to go back to being young again. I did dumber things than you’d think possible for a university graduate. That’s why I excused myself from the jury — paying off a porn star and claiming it as a business expense? Heck, I’ve made accounting mistakes, too. But — this is the beautiful 3 a.m. idea — you’ve got to have some disasters, the kind you walk away from, to notice the bluebird on your shoulder. My disaster was a series of falls I took while walking around Manhattan. I’m 81. I used to have a good jump shot from the free-throw circle, I have hit for extra bases in softball, but that was a long time ago. Now, as I walk through LaGuardia, men driving passenger carts stop and offer me a ride. I decline. They say, “Are you sure?”

I fell twice crossing 89th Street, once in the middle of the street, once at the curb. I misjudged the step, crashed down on my hands and knees and chin, and once I walked into a tree branch on the path around the Central Park Reservoir and got plonked on my keister, and each time strangers rushed to my side to ask if I was okay and I said I was and jumped up but now I see these falls were a turning point in my life. Once you come crashing down, there is no longer a need to have a smart opinion about everything; you’re simply part of the human race. Your job is to be a biped rather than a quad. As Scripture says, It is God who has made us, and not we ourselves; we are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.And so long as you can stand up and baa, you can do comedy. I have a good sense of sentence structure and my vocabulary is exemplary. Thanks to my aunts Elsie and Margaret, I speak clearly. They listened to me recite my verse in Sunday school and said, “We could understand every word.” From Ephesians and Ecclesiastes to stand-up comedy is a hop and a jump.

|

|

Life is so enjoyable once you no longer need to be cool. Once in an ER I sat in a curtained alcove in a blue gown and my undies and was closely examined by a neurologist who wrote something on her clipboard and I asked to see it and she gave it to me. It said, “Very pleasant 80 y.o. male, tall, well-developed, well-nourished, flat affect, awake, alert, and appropriate.” It described me so well, especially the “awake, alert, and appropriate” but I took exception to the “flat affect” — I felt euphoric. The embolism had landed in a rural grassy part of my brain, far from the bustling neuron metropolis, and when I considered other possible outcomes (O.P.O.), it was exhilarating.

So I feel awakened, more alert to the beauties of life, and the appropriate thing is to write about them. I don’t need to fall down again or be examined by a neurologist. I need to go do my work. I retired years ago and I’ve been busier ever since. Gotta run. Bye.

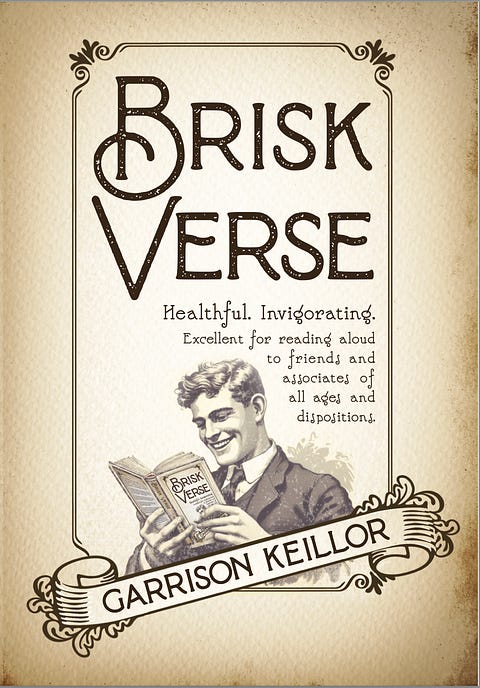

Garrison Keillor is in his Brisk Verse era. Buy his latest book and see for yourself!

CLICK HERE to buy a personalized copy today!